On The Ropes

“I don’t know if anyone realises, but GM-H damned nearly took care of Ford,” said former Ford Australian marketing/sales executive, Keith Horner.

Retiring in 1976 after 14 years at Broadmeadows and 42 years in the motor industry, Horner agreed to do a warts and all two-part interview for the long-out-of-print Motor Manual magazine.

He began with his account of Ford’s famous Falcon-Mobil 70,000 Mile Durability Run in 1965.

It was one of the highlights of his period at Ford, but what hadn’t been revealed until then was just how close this event came to ending Ford’s Australian operations.

To put it bluntly, if this crazy gamble hadn’t come off, there’s every chance Ford would have quit Australia for good.

Sales of the original ‘Aussie’ Falcon - the XK - were disappointing after its launch in 1960, because of suspension durability issues on rough roads and other mechanical gremlins stemming from its cheap-as-chips US origins. There was a wide-held perception of weakness in its construction; ‘tinny’ was a popular term and it was soon nicknamed the ‘Foul Can’.

The much-improved models that followed - the XL and XM series - struggled in showrooms under the weight of such entrenched public perceptions. And, to make sure it maintained its market dominance, GM-H had responded to the launch of the Falcon by simply refusing to increase its own retail prices.

“If they held the price of the Holden another year, they would have just about had Ford walking backwards,” says Horner.

So, the 1965 Durability Run was pretty much an act of desperation. It really was do or die. The idea came from Ford’s dynamic new marketing executive, Bill Bourke, who’d been head-hunted from his position as sales manager of Ford Canada by managing director Wallace Booth.

Booth, better known as ‘Wally’, was sent here in 1963 with an ultimatum from US head office - either get the Australian operations in the black or close them down. His background was as a Detroit number-cruncher, but he was smart enough to realise that what was really needed in Australia was a ‘big ideas’ man like Bill Bourke. Today we’d call him a ‘blue sky’ kind of guy. Bourke had worked in military intelligence after WWII which was handy, given that the commercial battle between Ford and Holden in Australia wasn’t that far removed from a combat zone!

Soon after he arrived in February 1965, Bourke announced that the new XP Falcon series would be launched in April with a 70,000-mile (112,000 km) Durability Run to show how tough and reliable the latest breed of Falcons really was.

The basic concept was that a team of new, stock-standard XP Falcons, powered by either the 170ci (2.8 litre) ‘Pursuit’ or the new 200ci (3.3 litre) ‘Super Pursuit’ inline sixes, would be driven non-stop over nine gruelling days.

To reach the 70,000-mile target (the combined distance covered by five cars over nine days) meant maintaining a punishing average speed of more than 70mph (112 km/h). According to CAMS regulations covering the event, six cars could be used but only five would be allowed on the track at any one time.

How Bill Bourke arrived at the five-car, nine-day, 70,000-mile target is a bit of a mystery. The distance was the equivalent of 140 Bathurst 500s! He could have chosen to drive five times around Australia, or gone to the moon and back, and had as much impact. In any case, his main aim was to get the general public talking positively about Ford and its latest Falcon product. And that goal was certainly achieved.

The word ‘durability’ was also a strange term. Australians were more accustomed to ‘reliability’ trials. In the end, most journos simply called it the ‘Nine Day Torture Test’. After reading the Ford press release and doing the sums, reporters must have thought the new American management team at Ford had gone nuts. And some of the Aussie staff at Broadmeadows would no doubt have agreed!

The Devil’s In The Detail

According to Horner, when Bill Bourke made the announcement he hadn’t personally inspected the proposed location; Ford’s new 700-hectare vehicle proving ground in the You Yangs near Geelong which had just been completed. The Run would launch the new facility, as well as the new XP Falcon series.

The test circuit at the You Yangs wasn’t a high-speed banked oval like they had in America (that facility wouldn’t be built at You Yangs until 1972) but a replica of a typical Australian

bitumen country road, including a steep 1-in-4 uphill gradient, some fast left and right-hand sweepers and a downhill S bend with a blind approach. There were 17 corners, a few off-camber, and no straight section longer than 400 yards (365 metres) making up its 2.268 mile

(3.65 km) total distance.

The circuit was designed primarily for vehicle testing at average touring speeds of 30-40mph (48-64km/h) - not the 70 mph-plus that was required for the Durability Run. The site was noted for its imposing natural rock formations, with some massive boulders sitting just metres from the edge of the track in many places.

The track’s bitumen surface hadn’t even been laid when Bourke announced the Run. This was scheduled to be finished just a few weeks before the start. In fact, it was completed only 10 days before and had not had time to properly cure. As a result, crumbling bitumen would be a constant worry throughout. A pothole on one corner had to be filled in during the event, with cars swerving at high speed each lap to avoid the road crew!

One suggestion that Bourke had assumed that the test would be taking place on the future banked super speedway is not necessarily accurate. Motoring writer Bill Tuckey, for one, says it’s highly unlikely that Bourke wouldn’t have been aware that this wasn’t the track being built in 1965.

Knowing Bourke’s character, what is more likely is that he had this brilliant idea, possibly in the middle of the night after a couple of scotches, then left it to others to deal with the realities, or else. One of those ‘others’ was Keith Horner.

“When I heard about it I was horrified because I knew what the thing (the track) was like,” he says. “And it wasn’t until we were too far committed that Bill Bourke came back from a trip to America and saw the test track. And boy, I tell you that if ever there was a worried man in Australia it was Bill Bourke.”

One of the first things to be done was to make hurried alterations to the back straight. This section included a row of ‘jiggle bars’ set into the surface for suspension testing. Another necessity was to set up a power supply.

There was no mains electricity, so all equipment would have to be powered by a network of generators which ran day and night.

There was only one building on site, so a virtual tent city was created to accommodate a population of around 100 drivers, crew, organisers and media. Two rows of caravans were towed in. The main source of external lighting was the floodlights erected near the Start-Finish line where the cars made their pit stops. There was no heating, so huge bonfires were lit at night to keep the mechanics warm. The site looked more like a Boy Scout jamboree than the location for a serious corporate event.

The target seemed impossible, but by then it was too late to cancel. The start date was definite - Saturday April 24, 1965. And as that day approached, this looked like being one of the biggest disasters in Ford’s corporate history.

“We had a couple of tall poppies visiting from US Ford product engineering and boy, they took care to get the hell out of the country on the Friday,” says Horner. “They thought this was going to be the biggest disaster and that someone’s neck was going on the block and they made sure they were not

going to be identified with it in any way.”

Things were not looking exactly upbeat when MD Wally Booth arrived on the Saturday morning to flag off the 70,000 Mile Durability Run at exactly 8.28am. He wasn’t aware, for example, that chief engineer Jim Martin had privately given the run only about a 30 per cent chance of success. If things went wrong, a huge media contingent was there to record every embarrassing, humiliating moment.

A Few Good Men

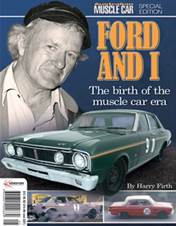

Yet somehow the Durability Run turned into a ‘howling success’ as Keith Horner liked to describe it. This was largely due to the efforts of two remarkable men; Harry Firth and Ford’s competitions manager Les Powell, who kept the thing going when it seemed to be almost jinxed.

Credit should also go to the team of drivers; some well known, some amateurs, and a team of mechanics led by the young John Sheppard. The panel beaters also performed minor miracles.

It was Ford’s competitions tuner/racer Harry Firth, fresh from winning the 1964 Ampol Trial and from preparing the team of all-conquering Cortina GTs at the 1964 Armstrong 500, who was given the job of preparing the six Ford Falcons. He, along with Les Powell, also had to recruit and train a team of drivers capable of driving these cars non-stop for nine days.

This was harder than anyone expected. Top guns like Ian Geoghegan and Bob Jane would only agree to brief ‘guest’ appearances. Most others soon realised that the novelty of driving a standard car over such a torturous circuit at such high speeds wore off after the first hour.

Firth worked out that the optimum lap time of 1 minute 52 seconds could be achieved with only one prod on the brakes at the end of the back straight. That was easy for him to say; the approved Firth technique required a level of skill that was beyond the average club competitor.

Firth had set a fastest lap time of 1 min 44.3s in practice in his standard Falcon coupe, only six seconds slower than his Bathurst car (Cortina GT) achieved in testing. During the event he was able to circulate lap after lap at 1:48, an average speed of 76 mph (122km/h). Lesser mortals were struggling to break two minutes!

Some of the drivers hired for the run turned up, had a look at the circuit and the facilities, and walked away. Others originally booked for the duration quit after only a day or two. It wasn’t a glamorous job. They were expected to drive for a couple of hours, try and grab a few hours sleep in one of the tiny caravans set up inside the circuit, then go back and do another shift.

The only escape was the food tent, where hot meals and coffee were served 24 hours a day by a notoriously grumpy cook. This was decades before today’s mobile phones, lap-top computers, Ipods, pay TV or the internet. There was no television, not even a public telephone. And everywhere you went was the buzzing of those bloody generators.

If the ambitious bid did fail, and it certainly looked like it might on several occasions, Les Powell was the man most likely to get the boot. He was in charge of the logistics, including fuel and tyres.

Mobil supplied the super fuel and ‘Mobiloil Special’ oil. Dunlop had agreed to supply its SP/41 tyres. Rubber - or lack of it - proved to be the first of Powell’s big problems. The fresh bitumen surface was so abrasive that the tyres were wearing out much faster than expected.

The offside fronts were down to the canvas after only 100 miles (160kms), although this situation improved once a layer of rubber started to build up on the bitumen. Even at their best, a set of tyres needed to be changed at every two-hour pit stop.

By the end of the first day, Dunlop’s man-on-the-spot Ross Dodson told Powell that he doubted that there were enough tyres in Melbourne to finish the run. He was seriously talking about pulling out.

Bill Bourke made an emergency visit, sat down with Dodson in a tent and calculated exactly how many sets of tyres were available in all other states of Australia. He told Dodson to get every tyre he could find and air-freight them in. By Monday, every Dunlop SP/41 in Australia was headed in the direction of the You Yangs! Even then, it was a close call. One report claimed there were only a few sets left at the finish…

While he was there, Bourke took a look at the deteriorating state of the cars and insisted that Les Powell order his drivers to show more discipline. It was obvious that some were treating the event as a series of races and trying to set lap times way beyond their ability.

At least three of the cars rolled during the proceedings (four according to some reports). One went straight into a rocky cutting wall. Within an hour, it was beaten back into shape and put back on the road.

Another went end-over-end five times. Another hit a two-tonne boulder so hard it moved it a couple of inches! These were critical incidents. There was only one spare Falcon and the CAMS rules stated that there had to be at least five cars on the track at all times. Even the spare one crashed.

Henry Ford II

Despite all the dramas throughout an immensely tough and draining eight days of non-stop driving, on the final Sunday (day eight) it looked like the impossible target would actually be met.

There was a surreal moment when a helicopter appeared on the horizon and landed at the site. Out stepped none other than chairman Henry Ford II; the top man himself on a brief visit to Australia. He’d heard about the run and demanded to see it for himself.

As another former Ford executive Max Grandsen put it: “he didn’t have to stay long to come to the conclusion that we were out of our bloody minds, and he left no one in any doubt that he thought we were a bunch of damn fools!”

Still, among the chaos and dust, a significant moment was captured on film. As Henry Ford II inspected the proceedings, he was invited to meet some of the drivers waiting in the pits. A man shown shaking hands with Ford was a young Allan Moffat, then virtually unknown.

He smiled, stood a polite distance away from Ford and bent forward at the waist to shake hands; the way you do when you greet royalty or the Pope. Who would have known that the young man with the geeky glasses would one day be Ford’s Australian superstar?

Two film documentaries were made about the event; one in colour, one in black and white. What is most noticeable in both is the continuous sound of those screaming Dunlop tyres. The footage shows that the Falcons were being driven right on the limit, usually with a touch of oversteer on the corners. Speeds of close to 100 mph (160km/h) were normal down the back straight, lap after lap, day and night. A few drivers said that driving at night was easier, because it made them focus on the road ahead with no distractions.

In the end, the choice of You Yangs for the run proved to be a masterstroke. The eerie beauty of the stark, remote landscape added greatly to the sense of drama. If the event had taken place on an artificial speed bowl, it wouldn’t have had half as much impact.

No spectators were allowed into the proving grounds for safety reasons, but television coverage turned this strange idea into a major sporting event. Updates of the day’s action were shown on the nightly news. Radio and newspapers also covered it. As the nine days unfolded, the whole nation became fascinated by the event.

While the Durability Run had initially looked like a corporate disaster waiting to happen, somehow it turned into a marketing masterpiece.

At 1.42 am on Monday, May 3 the first of the five Falcons crossed the line to complete the 70,000 miles, “without killing anyone” adds Horner, “which we were thankful for, because we weren’t sure we were going to do that at one stage. All the cars finished, bent and buckled, and it gave us a great advertising campaign. We sure put it on the line though, and there were no guarantees.”

‘Wild Bill’ MacLachlan, a Redex Trial veteran, was behind the wheel of Car No.3 when it broke the tape. This car was chosen because it was the least damaged. They finished in eight and three-quarter days, well ahead of time, then did some extra mileage to make sure.

The five Falcons averaged 71.3 mph (114 km/h) for the nearly nine days. A total of 49 new endurance records were set along the way, even though they were considered ‘provisional’ by CAMS.

Most important to Ford Australia, though, was that the embattled company had finally proved without doubt that the latest Falcons were more than up to the task of withstanding tough Australian conditions.

“We were able to go along to the fleets and talk to them again,” says Horner. “We loaned them cars for six months, just to prove to them what we had done at You Yangs. We told them, ‘At the end of six months, if you like it, buy it, and buy more like it, and they did.”

Brochures were produced, television commercials were made, even a vinyl record was released celebrating the event. The 70,000-mile run led to the XP Falcon range winning the 1965 Wheels Car of the Year award and resulted in increased sales and the long-term survival of Ford’s Australian operations. Ford was now able to claim in its promotional material that the

Falcon was “the only car to publicly prove its durability.”

Among the positive comments from the drivers was one by Bruce McPhee, a veteran Holden man who would go on to win the Bathurst 500 in a Monaro three years later. McPhee seemed genuinely surprised by the performance of the Falcons - “it rocked me to be absolutely honest, I’d always knocked them in the past.”

In one of the documentaries, a relieved Les Powell was interviewed shortly after the finish sitting in one of the caravans. Without his organisational skills, the event would never have succeeded. He looked exhausted and spoke slowly, as if he couldn’t quite believe the nightmare was finally over.

“We went out on a limb by saying we could do it,’ he said in a classic understatement. Some say old Les never quite recovered from the nine-day torture test. He retired soon after to run a pub in Geelong.

“It’s very unlikely anything like this will ever happen again,” said the commentator.

Nothing ever has.

Hell Drivers

One major problem for the organisers was the lack of suitable drivers. Les Powell had initially planned to use an elite squad of 22 high-profile racers, including Pete Geoghegan, Bob Jane, Kevin Bartlett, Barry Seton, Bruce McPhee, Brian Reed, ‘Wild Bill’ MacLachlan plus a relative newcomer called Allan Moffat who’d impressed in a Lotus Cortina at the previous year’s Sandown Six Hour race.

Harry Firth and John Raeburn would team up, as they had at the 1964 Armstrong 500,to drive the ‘hero’ car - the red No.1 Super Pursuit coupe.

The initial plan was to drive for two hours, then rest for four. This soon proved wildly optimistic and as drivers began to quit, the format was revised to ‘three hours on, three hours off’ with some doing crippling four-hour shifts. Not surprisingly, fatigue set in and even experienced endurance drivers began to lose concentration and crash.

In the end, Powell needed at least 32 drivers (some say the total was closer to 60) to keep the cars mobile over nine days.

The driving abilities of some of these newcomers were dubious at best. A number of amateurs were recruited at short notice by sticking up a notice at the offices of the Light Car Club in Melbourne. The only qualifications were that you had a current CAMS license and had driven in a rally or two.

Many of those who responded were too inexperienced for the high average speeds required or, worse still, saw this as a good opportunity to show how fast they were. They were soon sent home.

Towards the end, Les Powell was so desperate for capable drivers he sent out alerts to other states. Motoring writers Max Stahl and Bill Tuckey were already there covering the event, so they were recruited for a shift or two.

“I remember it was much scarier than any moment of the three Bathurst enduros I later drove,” says Tuckey.

The pros seemed to agree. Bob Jane claimed that his two shifts were harder than any Armstrong 500 race. Ern Abbott, a skilled Appendix J Valiant racer, admitted that he was terrified for the first 10 laps. “You go up in the air and all you can see is the sky and suddenly someone takes the road from underneath you.”

Redex Trials veteran MacLachlan described it as, “easily by far the toughest circuit I’ve driven on.” He said he was concentrating so hard that when his wife arrived and waved to him, he hadn’t noticed her.

“Now I know just how a one-armed paper-hanger must feel,” joked Bill Daly. On his first shift, Daly had forgotten to put on his driving gloves. During the next two hours he managed to pull them out of his pocket and place them on the seat beside him, but could never break his concentration for long enough to actually put them on!

Even the top drivers had accidents. That year’s Bathurst 500 winner, Barry Seton, rolled on two occasions after snapping axles and losing wheels – one of them end-over-end five times at 90 mph (145km/h)! He exited through the empty rear window.

John Roxburgh and Clive Millis rolled once each. Kevin Bartlett went off twice after blowing tyres. Very few didn’t have at least one major drama.

Other drivers mentioned in dispatches include Barry Arentz, Herb Taylor, Barry Topen, Bob Beasley, Bruce Corstorphan, Brian Reed, Geoff Russell, Gil Davis, Len Brennan, Max Volkers, Jon Leighton, Fred Gibson, Clive Millis, Brian Sampson, Allen Caelli and Tom Quill, who came over from South Australia for the opportunity.

The Famous Five - Plus One

Ford supplied five brand new Falcons for the Durability Run, plus one spare. They were all new XP series cars.

“Greater staying power in the engines. Extra strength in the gearbox. More steel in the springs. More lining in the brakes. Falcon is made more durable by triple rust protection, which includes a complete underbody dip. And only Falcon has ‘Torque-box’ chassis construction for tighter, huskier body,” boasted the brochure. Running them non-stop for nine days was a dramatic way to prove these claims.

All six cars were prepared by Harry Firth. Harry chose the red No.1 two-door coupe as his personal transport. It was a new 200 Super Pursuit automatic putting out 121 bhp, nicknamed ‘The Dreamboat’ by the other drivers.

The second 200 Super Pursuit automatic was No. 6, the black coupe used as the reserve vehicle. It was needed often and did as many miles as some of the others. The other four Falcon sedans, blue or white in colour, were ‘three on the tree’ 170 Pursuits putting out 111 bhp.

Firth set the fastest lap in his car, although young Barry Arentz got close to that on the final night in No. 3, a 170 nicknamed ‘Bluebird’. Arentz set several records on the final night, flying around with his high beams and fog lights blazing.

No. 3 was also driven by Bill MacLaughlin and Kevin Bartlett. Despite a few blown tyres, this car was the least damaged of the six, and chosen as the one to mark the finish of the marathon. It also covered the greatest distance - 14,123 miles (22,597kms) in total.

Still, it was Harry Firth’s ‘Dreamboat’ (which looked like it had been in a demolition derby and lost) which was chosen to be displayed in the foyer of Melbourne’s Southern Cross Hotel the following day.

With one side violently crushed, windows replaced by plastic sheeting and the doors crudely held shut by straps, the badly beaten-up XP somehow symbolised the whole crazy concept.

Big crowds came to see it and no doubt marvel at how indestructible Ford’s new XP Falcons really were. While most cars had some visible body damage, Ford claimed that there wasn’t one serious problem with either engines or transmissions. Mission accomplished!

.jpg&q=70&h=226&w=176&c=1&s=1)